HEAVEN ON EARTH

Words by DAVE SEMINARA

THE indonesian island of bali is a world apart where the warmth of the climate is only surpassed by the hospitality of the people. save seminara takes his family in search of off-the-beaten track experiences on "the island of the gods"

Travelers flock to Bali for its fascinating culture, the hospitality and warmth of its people, its ancient temples, pristine beaches, vibrant nightlife and hospitality – and, often, to find themselves. But as I stood at the prow of our “fast ferry" boat from the Gili Islands, just off the coast of Lombok, speeding past lush, densely forested coastline and colorfully painted jukung fishing boats towards the port of Padangbai, the main attraction of Bali was simply the chance to get the hell off that boat. For nearly three hours, we had endured a white-knuckle passage through rough seas, which was uncomfortable for me but nausea-inducing for my son, Leo, then nine years old, who spent much of the ride doubled over, ashen-faced.

Leo felt better the moment we stepped onto Balinese soil. But after six days in the sleepy, car- and scooter-free Gili Islands, I was at once fascinated and disoriented by the frenetic pace of Bali. Outside the ferry terminal, one driver held a sign with the words “I swear I’m cheap." Another held aloft a piece of card that read: “Taxi – fair price. I swear I’m fair.” Our driver, Wayan, had no sign, but gave us a primer on Balinese names and how they identify an individual’s place in their family or what their caste is. “When you meet someone like me, named Wayan, you know we are the oldest in our family," he said. Wayan explained that the Balinese don’t use family names but they often have a second given name that highlights a positive attribute. And if the family has more than four children, the name cycle repeats, so the fifth child in a family might be called “Another (Balik) Wayan."

The short lesson was a quick reminder that I had a lot to learn about Bali’s traditions. I had arrived on the so-called “Island of the Gods" with my family – wife, Jen, and two young boys, Leo and James, in tow – on a typically steamy day in July for a three-week working holiday, where my brief was to research and pen a column for the popular “36 Hours" series in the travel section of The New York Times. I had three weeks to find potential recommendations for ways travelers could spend a memorable weekend in Bali. But as we sat in a ferocious traffic jam amid armadas of slaloming mopeds, I worried that finding off-the-beaten-track experiences might be harder than I’d thought.

Bali has been beguiling Westerners since 1512, when Portuguese explorers first reached its northern coast. In 1597, the Dutch explorer Cornelis de Houtman arrived, and christened the island “Young Holland" while at anchor in Padangbai, where my journey began. Houtman befriended Bali’s king, the Dewa Agung, who is described in Miguel Covarrubias’ book Island of Bali as “a good-natured fat man who had 200 wives."

De Houtman’s sailors were as intrigued by local customs, such as the Ngaben – a 12-day cremation ceremony that is still common in Bali – as they were enchanted by the balmy climate and the comely Balinese women. After a few weeks on the island, two of Houtman’s crew literally jumped ship when it was time to go back to Holland. They settled in Gelgel, in Klungkung Province, married Balinese women, learned the language – and presumably wrote bestselling memoirs recording their transformational journeys of self-discovery. The rest of the crew returned to Holland with news of the “paradise" they had discovered in the East Indies.

Since then, foreigners have been falling hard for Bali. Mick Jagger married Jerry Hall here in 1990 in the modest home of a woodcarver, with a Hindu priest slitting the throat of a chicken and scattering its blood to purify the dwelling. David Bowie was so enamored that he specified in his will that he wanted a Balinese cremation ceremony, or, failing that, he wanted his ashes to be scattered across the island. (His family never confirmed if his wishes were granted.) Elizabeth Gilbert fell in love in Bali too, and her memoir Eat, Pray, Love has inspired untold readers to dream of following in her footsteps.

Understandably, those who “discover" Bali are often fanatical about keeping others out. In 1930, André Roosevelt, a photographer and cousin of US President Theodore Roosevelt, chronicled the “Western invasion" of the isle in the introduction to a book written by Hickman Powell called The Last Paradise. “This nation of artists is faced with a Western invasion and I cannot stand idly by and watch its destruction," he thundered. Nearly 60 years later, in 1989, the travel writer Pico Iyer expressed the paradox of Bali in his book Video Night in Kathmandu: “Bali was heaven, and hell was other people… it is the first vanity and goal of every traveler to come upon his own private pocket of perfection, it is his second vanity to close the door behind him."

Opening pages: Pura Ulun Danu Beratan temple on the shores of Lake Bratan, near Bedugul. Below: preparing “Canang Sari" floral prayer offerings. A regular sight in Bali, the baskets of petals are left as a tribute to the gods

Iyer wrote that Bali “remains unavoidable and irresistible" and said that those intent on finding the “real Bali" forsook the beaches and “flocked together off the beaten track in Ubud," which was our first base. We quickly realized that if Ubud (an hour and a half by car from the St. Regis Bali Resort) was off the beaten track in 1989, it certainly isn’t now. But if there’s one thing I’ve discovered in nearly half a century of wandering, it’s that if you find yourself surrounded by tourists, you have only yourself to blame. Often, the solution is to keep walking until you’re lost.

In wandering through the temples and neighborhoods of Ubud, what really stood out was the warmth and curiosity of everyone I encountered. Even people who were trying to sell me something – and failing – were almost absurdly polite and open to chatting. One afternoon, after I’d left a humble shop where we’d browsed but bought nothing, a woman from the store came chasing after us when we were already nearly three blocks away. My first instinct was to assume she was chasing after us with a “special price" offer, but, in fact, she had my camera slung across her shoulder. “Sorry, mister," she called out with a huge smile. “You forgot camera."

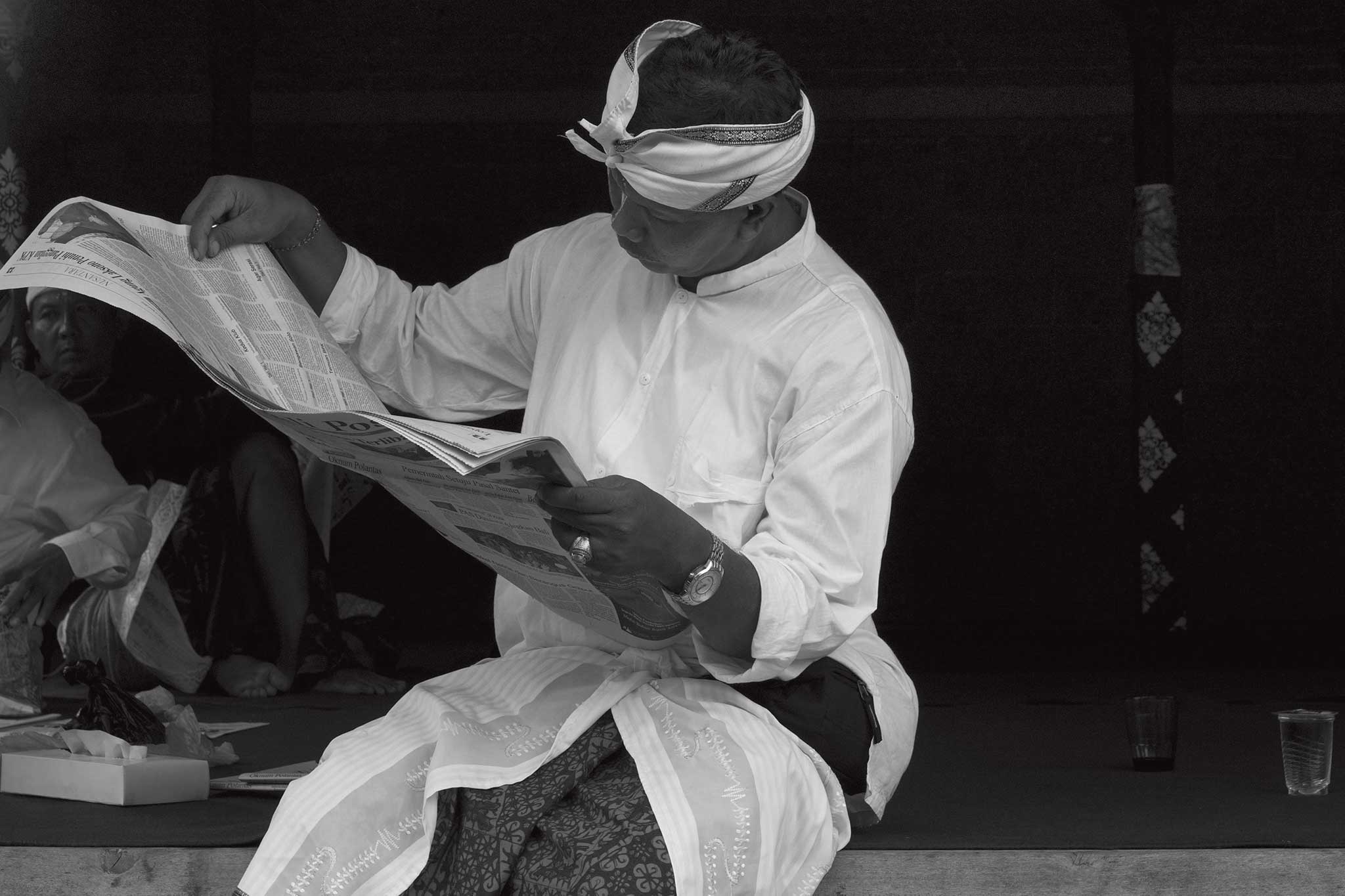

Later that same day, walking south along Jalan Raya Pengosekan near the center of Ubud, there were clusters of guesthouses, yoga studios, souvenir shops and warungs (casual restaurants.) But as I veered further south and then off onto the side streets one evening after the rest of my crew had already called it a night, I heard the distinctive high-pitched pinging of a traditional gamelan band in the distance. I followed my ears until I found myself in a courtyard where a band of perhaps a dozen men in richly embroidered red, black and gold costumes was rehearsing. I took a seat and was quickly lost in the music, which evoked a sense of the exotic Old Bali.

After their set, one of the younger members of the crew ambled over to me to introduce himself. His name was Kadek (“second born") and, like many Balinese, he wore many hats. In addition to playing in the gamelan band, he was also a painter and a driver. I told him I was interested in Bali’s history and he offered to take us to the Klungkung Palace the following day.

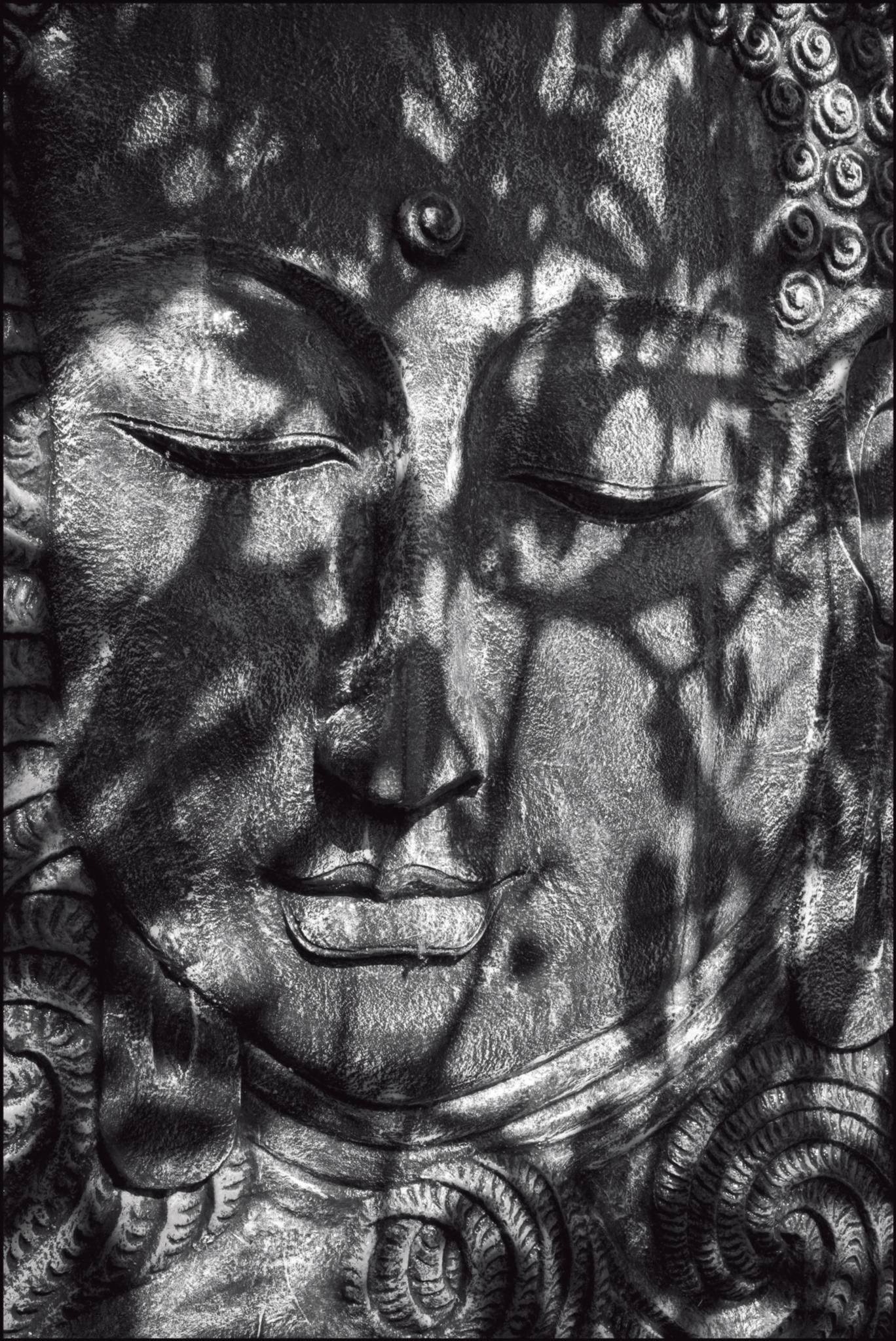

Kadek picked us up early. My sons strenuously objected to leaving at 8am but the plan was to avoid the hottest part of the day. A few miles east of the city, the traffic eased and we motored through villages full of small temples, unsupervised dogs and children playing in the streets. Klungkung, also called Puri Agung Semarapura, is a 17th-century palace that was once home to Bali’s most important line of kings. As the seat of power for the Klungkung Kingdom in the pre-colonial era, it’s a spectacular complex that served as a ceremonial meeting place and de facto court, where traditional justice (off with their heads!) was meted out by kings and their priests.

On April 18, 1908, as the Dutch tried to enforce a monopoly on opium trading, a Dutch soldier shot the rajah dead. His six wives and some 200 followers committed puputan, a mass ritual suicide, with kris swords, as Dutch troops burned most of the complex to the ground. We read about this grim story in the palace’s museum, which features photos of Balinese royalty, and artifacts such as the king’s chair, which is adorned with a lion, symbolizing his role as chief judge. But the palace’s real highlights are the spectacular ceiling paintings depicting scenes of punishment in hell and the joys of heaven in the Kertha Gosa Hall of Justice, one of two surviving floating pavilions. It’s a serene place, full of fountains, statues and evocative religious art. And, oddly enough, there is still a King of Klungkung. His name is Tjokorda Gde Agung, and he was crowned in 2010. The Royal family lived in exile in Lombok for more than 20 years after the 1908 massacre but came back in 1929 and have been here ever since. “Nice guy," Kadek said. I laughed. “No, really," he continued. “He’s here sometimes, greeting visitors. He likes to meet the people. Too bad he’s not around today."

A Abbas/Magnum Photos

A Abbas/Magnum Photos

In the days and weeks to follow, I fell into the habit of visiting one sight per day. Watching the sun set at Pura Uluwatu, a picturesque 11th century temple perched 825 feet above the Indian Ocean, was a particular highlight. One of Bali's six most significant temples, it has panoramic clifftop views and mischievous long tailed monkeys that make sport out of snagging items from tourists. On another occasion, we made an excursion to Pura Besakih, which has been one of Bali's most important temple complexes far more than two millennia. Although it's a tourist attraction, it's also an active place of worship where some 70 celebrations are held throughout the year.

During our time in Bali, we criss-crossed the island and discovered that it's larger than you think. Very few towns in the island's interior are 'overrun' with tourists, so there's plenty of terra incognita for intrepid travellers to explore and we found a wealth of good places to eat and lounge on the beach in the Legian Seminyak area. Ubud was full of life but the vibe was more hurry than hammock. I didn't really feel like I was on vacation until we reached Nusa Dua (where The St. Regis Bali Resort is situated) with its pristine beaches. But I hadn't come to Bali just to relax. I was looking for slices of Old Bali, authentic experiences I could share with like-minded travellers.

This led me in many directions around the island, and over and over again, my happiest moments revolved around interactions with local people, who all seemed delighted to meet us. Even negotiations could be charming. For example, my son James had his eye on a beautiful hand made ukulele at a music shop called lanshen in Legian. Balinese craftsman Ian Aiman didn't just sell us the instrument; he also wanted to teach James how to play it. "I am so happy this boy is getting my ukulele," he said.

Towards the end of our three weeks, we headed for a small town in East Bali called Sideman. It's a humble place, with one main street and a smattering of guesthouses and warungs set amid the incredibly green and lush rice paddies East Bali is famed for. It was here that we stumbled upon Pasraman Vidya Giri (PVG) a local charity that teaches children English and traditional Balinese arts - we heard gamelan drums one afternoon and were delighted to discover it was children the same age as my kids who were playing the instruments.

The goal of PVG is to teach Balinese children important aspects of their culture, to make sure it endures. But the kids are just as eager to teach visitors how to play the drums, make Hindu offerings, and take part in Balinese dances. My sons made friends with a host of teenage girls in the program who doted on them and put on a spectacular theatrical performance for us in full Balinese costume on our last night in Sideman. Later that night, I checked my Instagram account and noticed that I had several new Balinese friends, most of them following me so I could pass messages to my phoneless sons. One wrote, "When are Leo and James coming back to Bali?" And I realized then that Old Bali and New Bali are the same place - and both are unforgettable.

Your address: The St. Regis Bali Resort